Current Issues with Transfer Learning in NLP

Natural Language Processing (NLP) has recently witnessed dramatic progress with state-of-the-art results being published every few days. Leaderboard madness is diriving the most common NLP benchmarks such as GLUE and SUPERGLUE with scores that are getting closer and closer to human-level performance. Most of these results are driven by transfer learning from large scale datasets through super large (Billions of parameters) models. My aim in this article is to point out the issues and challenges facing transfer learning and point out some possible solutions to such problems.

Computational Intensity

The most successful form of Transfer Learning in NLP today is Sequential Transfer Learning (STL), which is typically employed in the form of Language Modeling Pre-training. Almost all SOTA results achieved recently have been mainly driven by a two-step scheme:

- Pre-train a monster model for Language Modeling on a large general-purpose corpus (The more data the better).

- Finetune the whole model (or a subset thereof) on the target task.

ELMO, BERT, GPT, GPT-2, XLNET and RoBERTa are all instances of the same technique. One major problem with these methods is the tremendous resource craveness. What I mean by resources is both data and compute power. For instance, it has been estimated that it costs around $250,000 to train XLNET on 512 TPU v3 chips with only 1-2% gain over BERT in 3/4 datasets.

This takes us to the next issue:

Difficult Reproducibility

Reproducibility is a already becoming a problem in machine learning research. For example, Dacrema et al.) analyzed 18 different proposed Neural-based Recommendation Systems and found that only 7 of them were reproducible with reasonable effort. Generally speaking, to be able to use or build upon a particular research idea, it’s imperative for that idea to be easily reproducible. With the substantial computational resources needed to train these huge NLP models and reproduce their results, small tech companies, startups, research labs and independent researchers will not be able to compete.

Task Leaderboards Are No Longer Enough

Anna Rogers argues in her blog post why more data & compute = SOTA is NOT research news. She argues that the main problem with leaderboards is that the rank of a model is totally dependent on its task score with no consideration given to the amount of data, compute or training time needed to achieve that score.

Here's a summary post on problems with huge models that dominate #NLProc these days. I put together several different discussion threads with/by @yoavgo, @jaseweston, @sleepinyourhat, @bkbrd, @alex_conneau, @SeeTedTalk. https://t.co/MokmmEYx91

— Anna Rogers (@annargrs) July 19, 2019

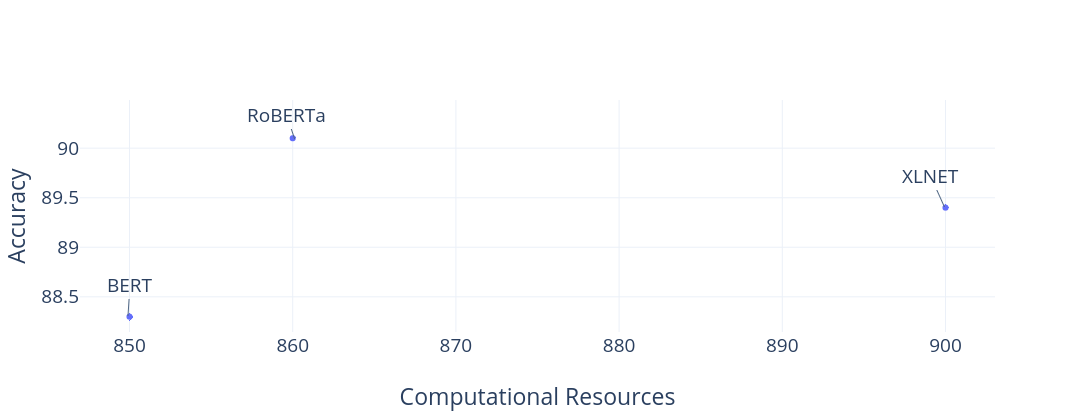

I suggest you check the above thread for various comments on the problem. Rohit Pgarg suggests comparing the performance of models on a two-dimensional scale of both task accuracy and computational resource. See the plot below. I suggest we add another dimension that corresponds to the amount of data the model has been trained on. However, this visualization will not provide an insight into which model is generally better. Also there’s a very interesting comment by Alexandr Savinov where he suggests to use how much of input information the algorithm is able to “pack” to one unit of output (model parameter) representation for one unit of CPU time.

|

|---|

| Using Computational Resource as an additional metric to task accuracy in comparing models performance |

It is not like How We Learn

Children learn language through noisy, ambiguous input and minimal supervision. A child can start to pick up the meaning of a word from just a few exposures to that word. This is very unlike the pretraining step used in STL settings where a model need to see millions of contexts including a specific word to grasp the meaning of the word. There is a very important question of whether it is possible to learn semantics from raw text only without any external supervision. If you’re interested in a twitter debate on this topic see this thread. If the answer is no, that means that pre-training these models does not actually give them true language understanding. While it’s true that we use transfer learning in our everyday life. For instance, if we know how to drive a manual car, it becomes very easy for us to utilize the acquired knowledge (such as of using the brakes and the gas pedal) to the task of driving an automatic car. But is that the path that we humans take towards language learning? Not likely. One might argue, however, that as long as an approach produces good results, whether it is similar or not to how humans learn does not actually matter. Unfortunately, some of the good results produced by these models are questionable as we will see in the next section.

From another perspective, humans assume a continual (lifelong) learning path towards language learning. Whenever we learn a new task, this learning usually does not interfere with previously learned tasks. On the other hand, the prevalent machine learning models (including transfer learning approaches) that are only trained on a single task usually fail to make use of previously aquired knowledge when the distrubtion of the new training data shifts— a phenomenon known as catastrophic forgetting (McCloskey et al., 1989), (d’Autume et al., 2019).

Shallow Language Understanding

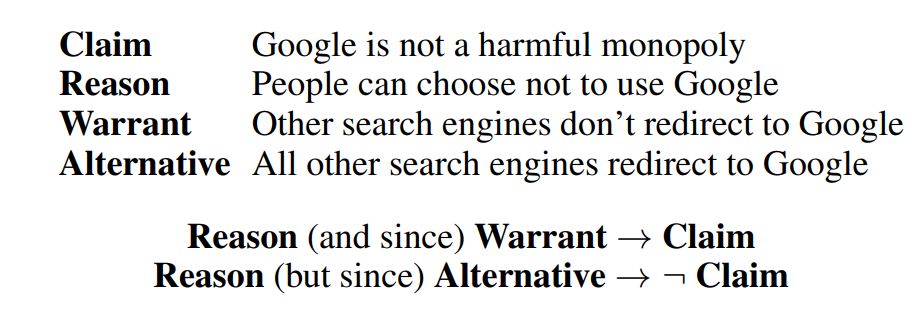

The language modeling task is indeed a complex task. Take for instance the sentence: “The man in the red shirt is running fast. He must be…” In order for the model to complete that sentence, the model has to understand what running fast usually implies i.e being in a hurry. So how deep do these pretrained models actually understand language? Unfortunately, not so much. Niven et al., 2019 analyze the performance of BERT on the Argument Reasoning and Comprehension task (ARCT) (Habernal et al., 2018). ARCT can be described as follows: Given a Claim $C$ and a Reason $R$, the task is to select the correct Warrant $W$ over another distractor, the alternative warrant $A$. The correct warrant satisfies $R \land C \rightarrow W$ while the alternative warrant satisfies $R \land C \rightarrow \neg A $. See the figure below.

|

|---|

| Sample of the Argument Reasoning and Comprehension Task. Source: (Niven et al., 2019) |

Remarkably, BERT achieves a very competitive accuracy of 77% on this task, which is only 3 points below the human baseline. At first, this would suggest that BERT has a quite strong reasoning ability. To investigate further, Niven et al., 2019 employed what is known as “probing”. That is, they finetuned BERT on this task, yet the input to BERT was only both the correct and the alternative warrants without exposing it to either the claim or the reason. The hypothesis is that if BERT relies on some statistical cues in the warrants, it should still perfom well even if it has only seen the warrants without any other information. Interestingly, their results show only a drop of 6% in accuracy over using both Reason and Claim. This suggests that BERT is not actually performing any type of reasoning but that the warrants themselves have sufficient cues for BERT to be able to reach such high accuracy. Remarkably, by replacing the test set with an adversarial one that is free of these cues the BERT relies on, BERT was only able to achieve an accuracy of 53%, which is just above random chance.

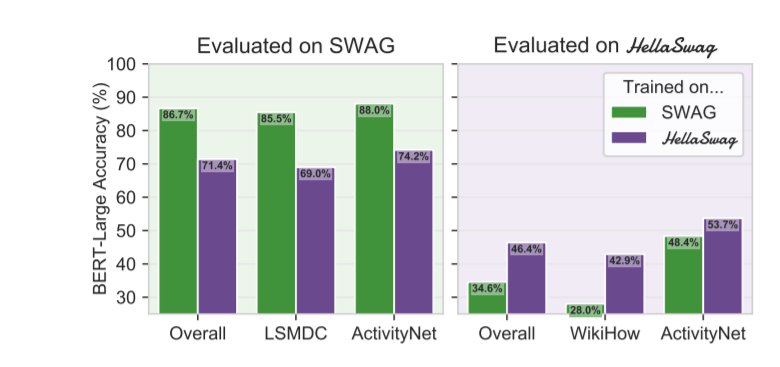

Another related paper is (Zellers et al., 2019) titled “Can a Machine Really Finish your Sentence?”. They consider the task of Commonsense Natural Language Inference where a machine should select the most likely follow up to given sentence. For instance,given the sentence: “The team played so well”, the system should select “They won the game” as a follow up. The authors argue that altough BERT was able to achieve almost 86% accuracy (only 2 points below human-baseline), such high accuracy is not due high-level form of reasoning on BERT’s side but due to BERT learning to pick up on dataset-specific distributional biases. They showed that by creating a more difficult dataset (HellaSwag) by means of Adversarial Filtering (which is a technique that aims to produce an adversarial dataset for any possible train, test split), BERT accuracy dropped to as low as 53%. The paper discusses the subtle distinction between Dataset Performance and Task Performance. Performing very well on a dataset for a specific task by no means indicates solving the underlying task.

|

|---|

| Performance of BERT on SWAG compare to HellaSwag. Source: (Zellers et al., 2019) |

Clearly, there is something going on here. Is it possible that BERT’s good results are actually driven by its ability to hijack the target datasets by leveraging various distributinoal cues and biases? Can more investigation into BERT’s results lead to other similar findings and conclusions? If so, then I believe we will not only need to build better models, but also better datasets. We need to have datsets that can actually reflect the difficuly of the underlying task rather than make it easy for the model to achieve deceiving accuracies and leaderboard scores.

High Carbon Footprint

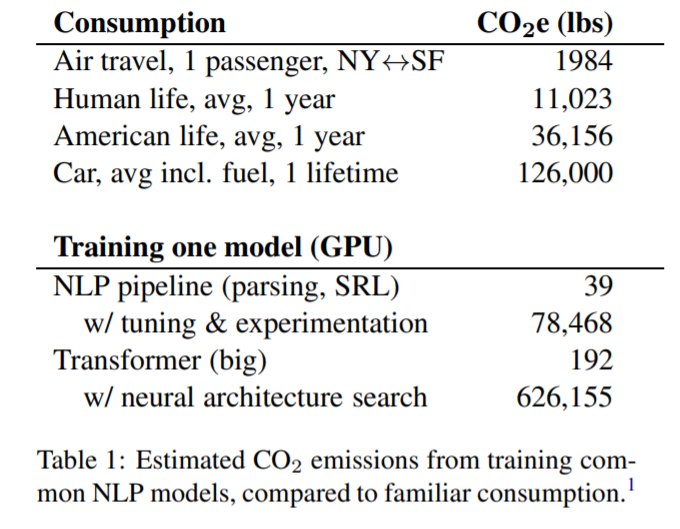

Believe it or not, but training these grandiose models has a negative effect on the environment. Strubell et al. compare the estimated $CO_2$ emissions from training Big Transformer architecture to emissions caused by other $CO_2$ sources. Suprisingly, training a single Transformer arhcitectue with neural architecture search emits approximately 6.0x the amount of $CO_2$ emitted through the lifetime of a car.

Schwartz et al. introduce what they call Green AI, which is the practice of making AI both more efficient and inclusive. Similar to what we discussed above, they strongly suggest adding efficiency as another metric alongside task accuracy. They also believe it’s necessary for research papers to include the “price tag” or the cost of model training. This should encourage the research towards more efficient and less resource-demanding model architectures.